http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/08/economist-explains-6

SOUTH KOREA, a dynamo of growth, is also afire with faith. This week Pope Francis will spend five days there, for Asian Youth Day and to beatify 124 early martyrs. About 5.4m of South Korea’s 50m people are Roman Catholics. Perhaps 9m more are Protestants, of many stripes. Yoido Full Gospel Church’s 1m members form the largest Pentecostal congregation on Earth. Belief’s farther shores include the Unification Church, soon to mark the anniversary of its founder Sun-myung Moon’s "ascension". The late Yoo Byung-eun, the shifty and versatile tycoon behind the ferry Sewol which sank in April, killing 304 mostly teenage passengers, had also founded his own sect (and the website God.com, now in other hands); its followers hid him during Korea’s largest-ever police man-hunt.

All this is particularly striking, because Asia is mostly stony ground for Christianity. Spanish rule left the Philippines strongly Catholic, but Korea is less simple. In the 18th century curious intellectuals encountered Catholicism in Beijing and smuggled it home. Confucian monarchs, brooking no rival allegiance, executed most early converts: hence all those martyrs, ranking Korea fourth globally for quantity of saints. Protestantism came later and fared better. By the 1880s Korea was opening up, and the mainly American missionaries made two astute moves: opening the first modern schools, which admitted girls; and translating the Bible into the vernacular Hangul Korean alphabet, then viewed as infra dig, rather than the Chinese characters favoured by literati.

The seeds thus sown incubated under Japan’s rule (1910-45), and have sprouted wildly since. The trauma of Japanese conquest eroded faith in Confucian or Buddhist traditions: Koreans could relate to Israel’s sufferings in the Old Testament (no Chosen jokes, please). Yet by 1945 only 2% of Koreans were Christian. The recent explosive growth accompanied that of the economy. Cue Weber’s Protestant ethic: for the conservative majority, worldly success connotes God’s blessing. But Korea also bred its own liberation theology (minjung), lauding the poor and oppressed. Rapid social change often produces spiritual ferment and entrepreneurs like Moon and Yoo: saviours for some, to others charlatans. Prophet and profit can blur: both men did time for fraud. Even Yoido’s founder, David Cho, was convicted in February of embezzling $12m. But these are rare outliers.

Today 23% of South Koreans are Buddhist and 46% profess no belief. Does this represent scope for Christianity's growth, or incipient secularisation? In 2012 only 52% claimed to be religious, down from 56% in 2005. But the world is now their oyster: only America sends more missionaries. Korean Christians have been seized in Afghanistan, beheaded in Iraq and stopped by their embassy from hymn-singing in Yemen. Many work undercover in China. Some, riskily, help North Koreans to flee: as many as 1,000 have reportedly had their Chinese visas cancelled. Others have a grander ambition, to spread Christianity in the North. In Japanese days Pyongyang was a Protestant hotbed, and now some are back, running the private Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, which since 2010 has been educating North Korea’s future elite; strictly no preaching. Given Korean Christians’ energy and tenacity, it is a sure prophecy that one day the Pyongyang skyline will be as studded with neon crosses as Seoul’s.

Thursday, October 02, 2014

Why so many Koreans are called Kim

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/09/economist-explains-5

A SOUTH KOREAN saying claims that a stone thrown from the top of Mount Namsan, in the centre of the capital Seoul, is bound to hit a person with the surname Kim or Lee. One in every five South Koreans is a Kim—in a population of just over 50m. And from the current president, Park Geun-hye, to rapper PSY (born Park Jae-sang), almost one in ten is a Park. Taken together, these three surnames account for almost half of those in use in South Korea today. Neighbouring China has around 100 surnames in common usage; Japan may have as many as 280,000 distinct family names. Why is there so little diversity in Korean surnames?

Korea’s long feudal tradition offers part of the answer. As in many other parts of the world, surnames were a rarity until the late Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). They remained the privilege of royals and a few aristocrats (yangban) only. Slaves and outcasts such as butchers, shamans and prostitutes, but also artisans, traders and monks, did not have the luxury of a family name. As the local gentry grew in importance, however, Wang Geon, the founding king of the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), tried to mollify it by granting surnames as a way to distinguish faithful subjects and government officials.

The gwageo, a civil-service examination that became an avenue for social advancement and royal preferment, required all those who sat it to register a surname. Thus elite households adopted one. It became increasingly common for successful merchants too to take on a last name. They could purchase an elite genealogy by physically buying a genealogical book (jokbo)—perhaps that of a bankrupt yangban—and using his surname. By the late 18th century, forgery of such records was rampant. Many families fiddled with theirs: when, for example, a bloodline came to an end, a non-relative could be written into a genealogical book in return for payment. The stranger, in turn, acquired a noble surname.

As family names such as Lee and Kim were among those used by royalty in ancient Korea, they were preferred by provincial elites and, later, commoners when plumping for a last name. This small pool of names originated from China, adopted by the Korean court and its nobility in the 7th century in emulation of noble-sounding Chinese surnames. (Many Korean surnames are formed from a single Chinese character.) So, to distinguish one’s lineage from those of others with the same surname, the place of origin of a given clan (bongwan) was often tagged onto the name. Kims have around 300 distinct regional origins, such as the Gyeongju Kim and Gimhae Kim clans (though the origin often goes unidentified except on official documents). The limited pot of names meant that no one was quite sure who was a blood relation; so, in the late Joseon period, the king enforced a ban on marriages between people with identical bongwan (a restriction that was only lifted in 1997). In 1894 the abolition of Korea’s class-based system allowed commoners to adopt a surname too: those on lower social rungs often adopted the name of their master or landlord, or simply took one in common usage. In 1909 a new census-registration law was passed, requiring all Koreans to register a surname.

Today clan origins, once deemed an important marker of a person’s heritage and status, no longer bear the same relevance to Koreans. Yet the number of new Park, Kim and Lee clans is in fact growing: more foreign nationals, including Chinese, Vietnamese and Filipinos, are becoming naturalised Korean citizens, and their most popular picks for a local surname are Kim, Lee, Park and Choi, according to government figures; registering, for example, the Mongol Kim clan, or the Taeguk (of Thailand) Park clan. The popularity of these three names looks set to continue.

A SOUTH KOREAN saying claims that a stone thrown from the top of Mount Namsan, in the centre of the capital Seoul, is bound to hit a person with the surname Kim or Lee. One in every five South Koreans is a Kim—in a population of just over 50m. And from the current president, Park Geun-hye, to rapper PSY (born Park Jae-sang), almost one in ten is a Park. Taken together, these three surnames account for almost half of those in use in South Korea today. Neighbouring China has around 100 surnames in common usage; Japan may have as many as 280,000 distinct family names. Why is there so little diversity in Korean surnames?

Korea’s long feudal tradition offers part of the answer. As in many other parts of the world, surnames were a rarity until the late Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). They remained the privilege of royals and a few aristocrats (yangban) only. Slaves and outcasts such as butchers, shamans and prostitutes, but also artisans, traders and monks, did not have the luxury of a family name. As the local gentry grew in importance, however, Wang Geon, the founding king of the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), tried to mollify it by granting surnames as a way to distinguish faithful subjects and government officials.

The gwageo, a civil-service examination that became an avenue for social advancement and royal preferment, required all those who sat it to register a surname. Thus elite households adopted one. It became increasingly common for successful merchants too to take on a last name. They could purchase an elite genealogy by physically buying a genealogical book (jokbo)—perhaps that of a bankrupt yangban—and using his surname. By the late 18th century, forgery of such records was rampant. Many families fiddled with theirs: when, for example, a bloodline came to an end, a non-relative could be written into a genealogical book in return for payment. The stranger, in turn, acquired a noble surname.

As family names such as Lee and Kim were among those used by royalty in ancient Korea, they were preferred by provincial elites and, later, commoners when plumping for a last name. This small pool of names originated from China, adopted by the Korean court and its nobility in the 7th century in emulation of noble-sounding Chinese surnames. (Many Korean surnames are formed from a single Chinese character.) So, to distinguish one’s lineage from those of others with the same surname, the place of origin of a given clan (bongwan) was often tagged onto the name. Kims have around 300 distinct regional origins, such as the Gyeongju Kim and Gimhae Kim clans (though the origin often goes unidentified except on official documents). The limited pot of names meant that no one was quite sure who was a blood relation; so, in the late Joseon period, the king enforced a ban on marriages between people with identical bongwan (a restriction that was only lifted in 1997). In 1894 the abolition of Korea’s class-based system allowed commoners to adopt a surname too: those on lower social rungs often adopted the name of their master or landlord, or simply took one in common usage. In 1909 a new census-registration law was passed, requiring all Koreans to register a surname.

Today clan origins, once deemed an important marker of a person’s heritage and status, no longer bear the same relevance to Koreans. Yet the number of new Park, Kim and Lee clans is in fact growing: more foreign nationals, including Chinese, Vietnamese and Filipinos, are becoming naturalised Korean citizens, and their most popular picks for a local surname are Kim, Lee, Park and Choi, according to government figures; registering, for example, the Mongol Kim clan, or the Taeguk (of Thailand) Park clan. The popularity of these three names looks set to continue.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

As succession looms at Samsung, much has to change

http://www.economist.com/news/business/21620195-succession-looms-korean-conglomerate-much-has-change-waiting-wings

“CHANGE everything except your wife and children.” Thus spoke Lee Kun-hee, the boss of Samsung, two decades ago at an emergency meeting with his senior managers. He wanted the conglomerate (whose name means “Three Stars”, implying that it would be huge and eternal) to stop churning out vast quantities of cheap products and focus on quality, to become one of the world’s leading firms.

Mr Lee (pictured, left) accomplished his mission, probably beyond his wildest dreams. Today the Samsung group, whose 74 companies have estimated annual revenues of more than 400 trillion won ($387 billion) and 369,000 employees, is into everything from washing-machines and holiday resorts to container ships and life insurance. But it is the group’s predominant electronics division that has made its patriarch particularly proud: Samsung has overtaken its Japanese rivals to become the world leader in this industry by revenues, outselling everyone in memory chips, flat-panel televisions and smartphones.

Now Samsung is again at a point in its 76-year history at which much has to change. This will be underlined if, as expected, Samsung Electronics issues a fresh profit warning shortly. The company is not facing existential threats. But the world around it is in flux, and Samsung has to adapt—from top to bottom.

Start at the top. In May Mr Lee, 72 years old, suffered a heart attack. He is still in hospital. Nobody expects him to return as he did in 2010, when he came back after avoiding prison for embezzlement and tax evasion. (He got off with a suspended sentence of three years and was later pardoned so he could remain a member of the International Olympic Committee.)

Mr Lee’s only son, Lee Jae-yong (pictured, right), looks certain to take control of Samsung’s main businesses, and his two daughters will run some smaller ones. The younger Mr Lee, now 46, joined Samsung Electronics in 2001 and ten years later had the title of vice-chairman. Other than a few bare biographical facts, little is known about him. “He is unproven as a manager,” says Chang Sea-jin, a business-school professor and author of “Sony vs Samsung”, a book about the two Asian tech giants. Despite Samsung’s best PR efforts, most Koreans still associate him with eSamsung, a disastrous internet venture.

Those who have met him call him approachable and unassuming—quite unlike his father, who is known for an imperial management style. When the elder Mr Lee visited factories, the red carpet was rolled out and employees were not allowed to look down on him from the windows. In 1995 he had thousands of faulty mobile phones and other devices burned and bulldozed in front of weeping employees.

His son’s more restrained personality may be just what Samsung Electronics, in particular, now needs. To thrive it must attract flighty technical talent and get along with partners. Sent to Silicon Valley to negotiate with Apple, a big customer for Samsung’s chips (and a rival in smartphones), young Mr Lee apparently managed to get along with the often prickly Steve Jobs. He was the only Samsung executive to be invited to Jobs’s memorial service.

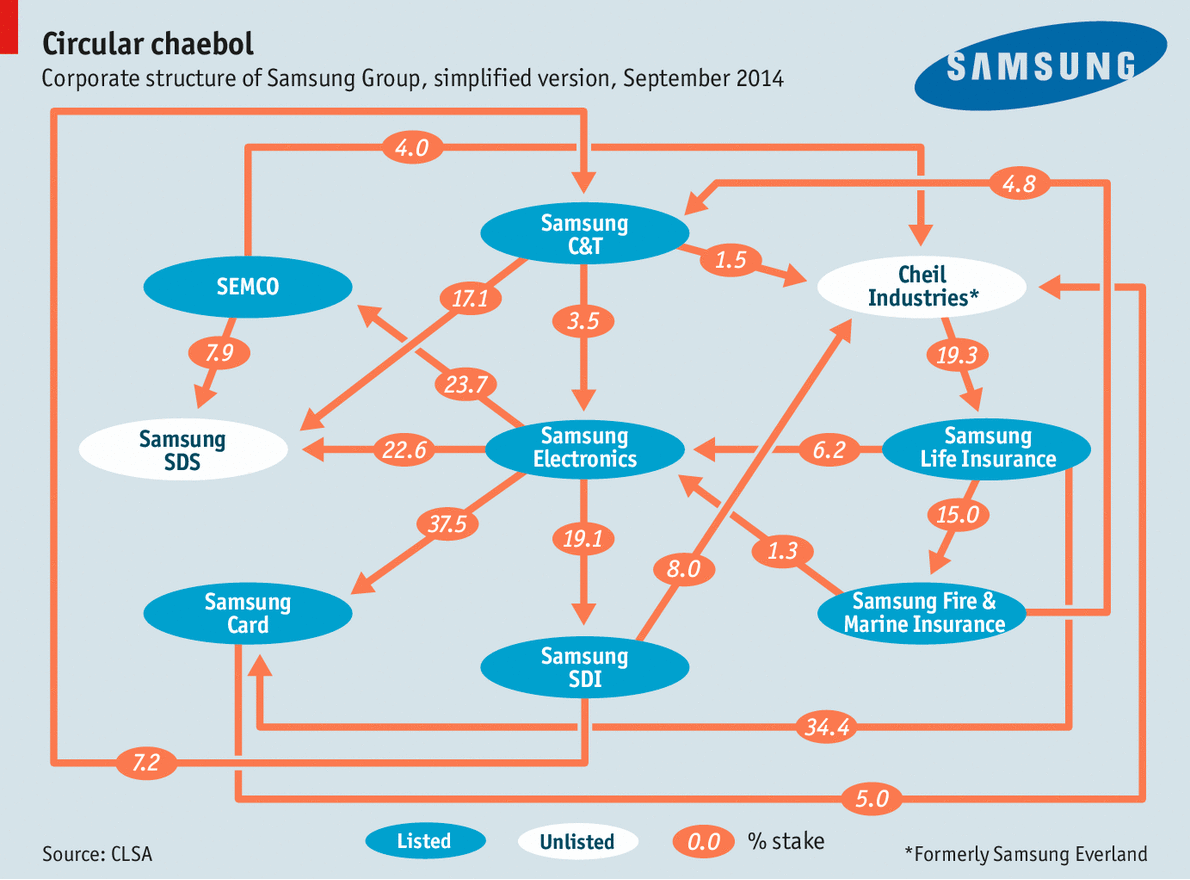

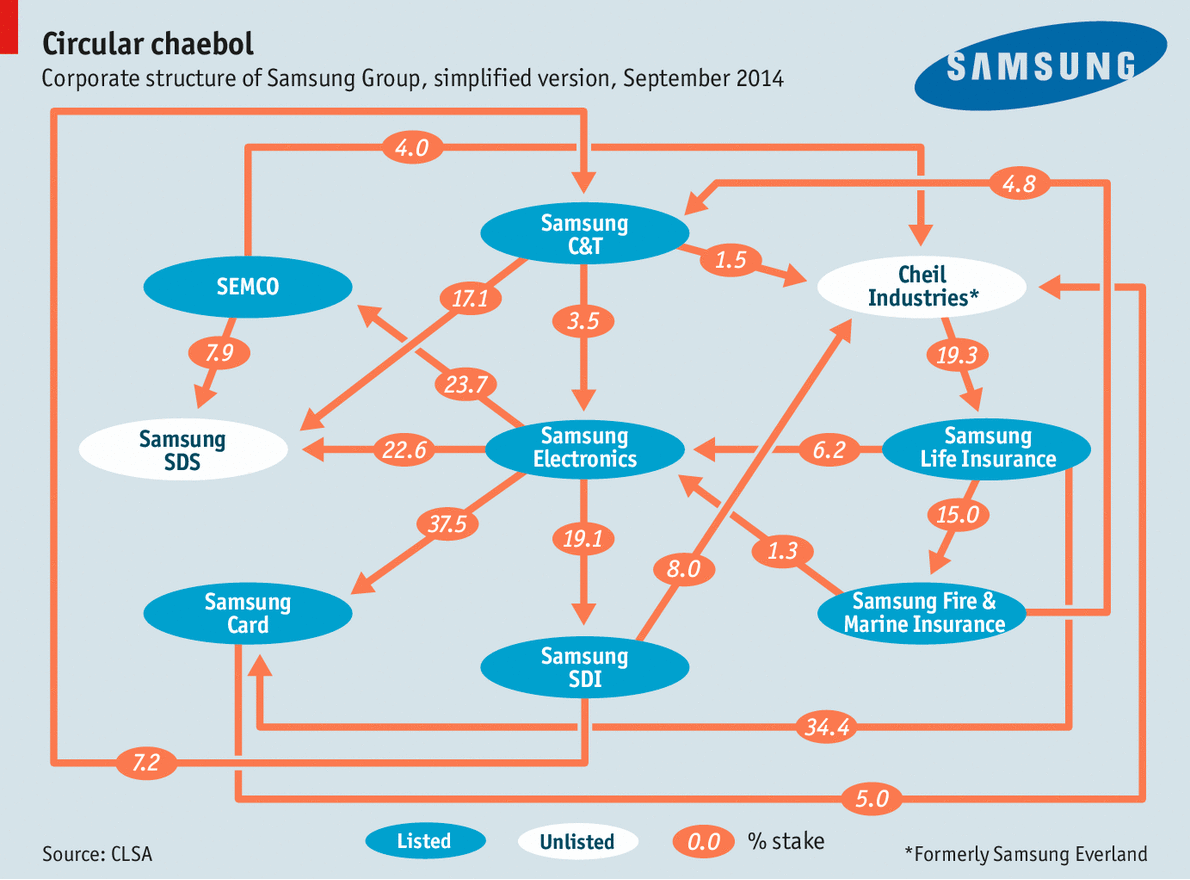

The succession is unlikely to happen before another badly needed change is well under way: reforming the group’s Byzantine corporate structure. For example, the group’s holding company, which has just changed its name from Samsung Everland to Cheil Industries, owns 19.3% of Samsung Life, which owns 34.4% of Samsung Card, which owns 5% of Cheil. (See the illustration below for a simplified depiction.)

This corporate hairball has let the Lees exert control over the group with a stake of less than 2%. But for various reasons they are now likely to simplify it, explains Shaun Cochran, a longtime Samsung-watcher at CLSA, a broker. One is that the rules against such circular shareholding structures are being tightened. But the most immediate consideration is the imminent succession—and the resulting inheritance tax. The family will have to pay about six trillion won, according to some estimates, and needs to raise cash.

This also goes a long way towards explaining why Samsung denies any talk of a restructuring: the more it seems a sure thing, the higher the share price and thus the tax bill. Because of the complex ownership structures, some listed companies within the group trade at a discount. When news broke of the older Mr Lee’s heart attack, the shares of Samsung Electronics went up—mainly because a restructuring was seen as more likely.

Denials notwithstanding, the restructuring has clearly begun. Earlier this month Samsung Heavy Industries and Samsung Engineering announced plans to merge. This will be followed by the IPOs of Samsung SDS, a provider of IT services, perhaps as early as November, and of Cheil, which is expected early next year.

The flotation of Cheil is key, argues Mr Cochran. Unlike other group companies it is controlled directly by the Lee children and a family foundation. The listings will not only raise cash, but also make it easier to put values on the group’s cross-shareholdings. So it will be easier to unpick these without attracting lawsuits.

The sooner all this happens, the better: the restructuring is distracting executives from running their businesses. One, in particular, needs attention: smartphones. Not only has it been directly responsible for a big chunk of the profits at Samsung Electronics, and thus the group; it is also the biggest customer for other parts of the business, such as making chips and displays.

Samsung Electronics came from nowhere in the space of a few years, to grab one-third of the market for smartphones in 2012. It did so mainly by being among the first to bet on Android, Google’s popular mobile operating system, and by offering iPhone-like handsets at lower prices than Apple. Yet since then, problems have been piling up, and Samsung’s market share has now slipped to 25%, reckons IDC, a market-research firm. The Galaxy 5S, which Samsung introduced in January, was derided for its cheap plastic casing.

Low-cost makers from China, such as Xiaomi and Huawei, and new European brands such as Wiko and Archos, are attacking Samsung’s market from below. From above, Apple has regained share, and looks set to keep doing so after its recent launch of a “phablet”, a phone with a large screen—a category where Samsung still had an advantage. What is more, the smartphone market is maturing; indeed, in Britain it is already shrinking.

If fighting back were simply a question of making better hardware, Samsung would be safe. This is what it knows best, says Ben Wood of CCS Insight, another market researcher. Since it launched Galaxy Gear, a smart watch, a year ago, it has followed up with five further models. “Samsung is prototyping in public,” says Mr Wood. But smart watches also show why Samsung is in trouble. The Apple Watch, launched at the same time as the bigger iPhone, may look a lot like the Galaxy Gear, but it comes embedded in an ecosystem of software and services, such as a new touchless payment system and sophisticated health-monitoring apps.

Samsung will have a hard time matching such an ecosystem. It does not control Android, and an effort to establish its own mobile operating system, Tizen, seems to have been put on the back burner. Being structurally a hardware company, and one with a conformist Confucian culture, Samsung would surprise many if it suddenly came up with great apps and services.

So, the firm’s best chance is to stick with gadgets, and to try to create ones that consumers love so much that they fly off the shelves, argues Francisco Jeronimo of IDC. But it has to act fast. The fates of Nokia and BlackBerry (which made another attempt at a comeback on September 24th by launching a new smartphone, the Passport) show how quickly fortunes can reverse. And Apple sold 10m of its new iPhones, including an updated smaller model, in three days—a number that the Galaxy 5S only reached after 25 days.

In all, the younger Mr Lee has his work cut out for him. Samsung-watchers wonder if he has it in him, but when he takes over he may have to make a “change everything” speech of his own.

Samsung

Waiting in the wings

As succession looms at the Korean conglomerate, much has to change

“CHANGE everything except your wife and children.” Thus spoke Lee Kun-hee, the boss of Samsung, two decades ago at an emergency meeting with his senior managers. He wanted the conglomerate (whose name means “Three Stars”, implying that it would be huge and eternal) to stop churning out vast quantities of cheap products and focus on quality, to become one of the world’s leading firms.

Mr Lee (pictured, left) accomplished his mission, probably beyond his wildest dreams. Today the Samsung group, whose 74 companies have estimated annual revenues of more than 400 trillion won ($387 billion) and 369,000 employees, is into everything from washing-machines and holiday resorts to container ships and life insurance. But it is the group’s predominant electronics division that has made its patriarch particularly proud: Samsung has overtaken its Japanese rivals to become the world leader in this industry by revenues, outselling everyone in memory chips, flat-panel televisions and smartphones.

Now Samsung is again at a point in its 76-year history at which much has to change. This will be underlined if, as expected, Samsung Electronics issues a fresh profit warning shortly. The company is not facing existential threats. But the world around it is in flux, and Samsung has to adapt—from top to bottom.

Start at the top. In May Mr Lee, 72 years old, suffered a heart attack. He is still in hospital. Nobody expects him to return as he did in 2010, when he came back after avoiding prison for embezzlement and tax evasion. (He got off with a suspended sentence of three years and was later pardoned so he could remain a member of the International Olympic Committee.)

Mr Lee’s only son, Lee Jae-yong (pictured, right), looks certain to take control of Samsung’s main businesses, and his two daughters will run some smaller ones. The younger Mr Lee, now 46, joined Samsung Electronics in 2001 and ten years later had the title of vice-chairman. Other than a few bare biographical facts, little is known about him. “He is unproven as a manager,” says Chang Sea-jin, a business-school professor and author of “Sony vs Samsung”, a book about the two Asian tech giants. Despite Samsung’s best PR efforts, most Koreans still associate him with eSamsung, a disastrous internet venture.

Those who have met him call him approachable and unassuming—quite unlike his father, who is known for an imperial management style. When the elder Mr Lee visited factories, the red carpet was rolled out and employees were not allowed to look down on him from the windows. In 1995 he had thousands of faulty mobile phones and other devices burned and bulldozed in front of weeping employees.

His son’s more restrained personality may be just what Samsung Electronics, in particular, now needs. To thrive it must attract flighty technical talent and get along with partners. Sent to Silicon Valley to negotiate with Apple, a big customer for Samsung’s chips (and a rival in smartphones), young Mr Lee apparently managed to get along with the often prickly Steve Jobs. He was the only Samsung executive to be invited to Jobs’s memorial service.

The succession is unlikely to happen before another badly needed change is well under way: reforming the group’s Byzantine corporate structure. For example, the group’s holding company, which has just changed its name from Samsung Everland to Cheil Industries, owns 19.3% of Samsung Life, which owns 34.4% of Samsung Card, which owns 5% of Cheil. (See the illustration below for a simplified depiction.)

This corporate hairball has let the Lees exert control over the group with a stake of less than 2%. But for various reasons they are now likely to simplify it, explains Shaun Cochran, a longtime Samsung-watcher at CLSA, a broker. One is that the rules against such circular shareholding structures are being tightened. But the most immediate consideration is the imminent succession—and the resulting inheritance tax. The family will have to pay about six trillion won, according to some estimates, and needs to raise cash.

This also goes a long way towards explaining why Samsung denies any talk of a restructuring: the more it seems a sure thing, the higher the share price and thus the tax bill. Because of the complex ownership structures, some listed companies within the group trade at a discount. When news broke of the older Mr Lee’s heart attack, the shares of Samsung Electronics went up—mainly because a restructuring was seen as more likely.

Denials notwithstanding, the restructuring has clearly begun. Earlier this month Samsung Heavy Industries and Samsung Engineering announced plans to merge. This will be followed by the IPOs of Samsung SDS, a provider of IT services, perhaps as early as November, and of Cheil, which is expected early next year.

The flotation of Cheil is key, argues Mr Cochran. Unlike other group companies it is controlled directly by the Lee children and a family foundation. The listings will not only raise cash, but also make it easier to put values on the group’s cross-shareholdings. So it will be easier to unpick these without attracting lawsuits.

The sooner all this happens, the better: the restructuring is distracting executives from running their businesses. One, in particular, needs attention: smartphones. Not only has it been directly responsible for a big chunk of the profits at Samsung Electronics, and thus the group; it is also the biggest customer for other parts of the business, such as making chips and displays.

Samsung Electronics came from nowhere in the space of a few years, to grab one-third of the market for smartphones in 2012. It did so mainly by being among the first to bet on Android, Google’s popular mobile operating system, and by offering iPhone-like handsets at lower prices than Apple. Yet since then, problems have been piling up, and Samsung’s market share has now slipped to 25%, reckons IDC, a market-research firm. The Galaxy 5S, which Samsung introduced in January, was derided for its cheap plastic casing.

Low-cost makers from China, such as Xiaomi and Huawei, and new European brands such as Wiko and Archos, are attacking Samsung’s market from below. From above, Apple has regained share, and looks set to keep doing so after its recent launch of a “phablet”, a phone with a large screen—a category where Samsung still had an advantage. What is more, the smartphone market is maturing; indeed, in Britain it is already shrinking.

If fighting back were simply a question of making better hardware, Samsung would be safe. This is what it knows best, says Ben Wood of CCS Insight, another market researcher. Since it launched Galaxy Gear, a smart watch, a year ago, it has followed up with five further models. “Samsung is prototyping in public,” says Mr Wood. But smart watches also show why Samsung is in trouble. The Apple Watch, launched at the same time as the bigger iPhone, may look a lot like the Galaxy Gear, but it comes embedded in an ecosystem of software and services, such as a new touchless payment system and sophisticated health-monitoring apps.

Samsung will have a hard time matching such an ecosystem. It does not control Android, and an effort to establish its own mobile operating system, Tizen, seems to have been put on the back burner. Being structurally a hardware company, and one with a conformist Confucian culture, Samsung would surprise many if it suddenly came up with great apps and services.

So, the firm’s best chance is to stick with gadgets, and to try to create ones that consumers love so much that they fly off the shelves, argues Francisco Jeronimo of IDC. But it has to act fast. The fates of Nokia and BlackBerry (which made another attempt at a comeback on September 24th by launching a new smartphone, the Passport) show how quickly fortunes can reverse. And Apple sold 10m of its new iPhones, including an updated smaller model, in three days—a number that the Galaxy 5S only reached after 25 days.

In all, the younger Mr Lee has his work cut out for him. Samsung-watchers wonder if he has it in him, but when he takes over he may have to make a “change everything” speech of his own.

Saturday, May 24, 2014

Korean men are marrying foreigners more from choice than necessity

http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21602761-korean-men-are-marrying-foreigners-more-choice-necessity-farmed-out

IN THE mid-1990s posters plastered on the subway in Seoul, South Korea’s capital, exhorted local girls to marry farmers. Young women had left their villages in droves since the 1960s for a better life in the booming city. Sons, however, stayed behind to tend family farms and fisheries.

The campaign was futile. Last year over a fifth of South Korean farmers and fishermen who tied the knot did so with a foreigner. The province of South Jeolla has the highest concentration of international marriages in the country—half of those getting married at the peak a decade ago. In those days, the business of broking unions with Chinese or South-East Asian women boomed, with matches made in the space of a few days. Not long ago placards in the provinces sang the praises of Vietnamese wives “who never run away”. Now, on the Seoul subway, banners encourage acceptance of multicultural families.

They are expected to exceed 1.5m by 2020, in a population of 50m. That is remarkable for a country that has long prided itself on its ethnic uniformity. But a preference for sons has led to a serious imbalance of the sexes. In 2010 half of all middle-aged men in South Korea were single, a fivefold increase since 1995. The birth rate has fallen to 1.3 children per woman of childbearing age, down from six in 1960. It is one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. Without immigration, the country’s labour force will shrink drastically.

The government is the biggest enthusiast for a multi-ethnic country. Its budget for multicultural families has shot up 24-fold since 2007, to 107 billion won ($105m). Some 200 support centres offer interpreting services, language classes, child care and counselling. School textbooks now include a section on mixed-race families. And in 2012 mixed-race Koreans could join the army for the first time. When four Mongolians working illegally in South Korea pulled a dozen Korean colleagues from a fire in 2007, locals urged the government to grant them residency (it did).

Still, assimilation remains elusive. Four in ten mixed-race marriages break down in the first five years, according to a survey by the Korean Women’s Development Institute, a think-tank. In 2009 almost a fifth of children from mixed-race households who should have been in school were not. Many mothers have limited Korean. And discrimination lurks.

The government is now tightening up the marriage rules. Last month two new requirements came into force: a foreign bride must speak Korean, and a Korean groom must support her financially. Koreans are now limited to a single marriage-visa request every five years.

Critics say making marriage more difficult will only serve to speed up the greying of the workforce. The pool of eligible women will shrink, says Lee In-su, a marriage broker in Daegu in the south-east. Most foreign brides come from rural areas lacking language schools. Meanwhile, competition for brides from China, where men also outnumber women, is fierce.

In fact, the number of Korean men taking foreign brides is dropping, from 31,000 a year in 2005 to 18,000 last year. And nine-tenths of matches are now urban, says Mr Lee. Vietnamese girls no longer want to languish in the Korean countryside, says Kim Young-shin of the Korea-Vietnam Cultural Centre in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital. They like watching Korean dramas and listening to K-pop—urban pursuits.

As for Korean clients, says Lee Chang-min, a broker in Seoul, they are increasingly better educated and better-off; some are among the country’s top earners. Many are simply on lower rungs of the eligibility ladder in a culture captivated by credentials, whether in looks, age or family connections.

Others, Mr Lee says, are wary of the stereotype of the doenjangnyeo (a disparaging term for a class of Korean women seen as latte-loving gold-diggers). They prefer a wife who can assume a more traditional role than one many Korean women are nowadays willing to play. These men, the brokers lament, are now more likely to be introduced to their foreign wives through friends than through brokers. Perhaps a modest win for melting-pot Korea after all.

IN THE mid-1990s posters plastered on the subway in Seoul, South Korea’s capital, exhorted local girls to marry farmers. Young women had left their villages in droves since the 1960s for a better life in the booming city. Sons, however, stayed behind to tend family farms and fisheries.

The campaign was futile. Last year over a fifth of South Korean farmers and fishermen who tied the knot did so with a foreigner. The province of South Jeolla has the highest concentration of international marriages in the country—half of those getting married at the peak a decade ago. In those days, the business of broking unions with Chinese or South-East Asian women boomed, with matches made in the space of a few days. Not long ago placards in the provinces sang the praises of Vietnamese wives “who never run away”. Now, on the Seoul subway, banners encourage acceptance of multicultural families.

They are expected to exceed 1.5m by 2020, in a population of 50m. That is remarkable for a country that has long prided itself on its ethnic uniformity. But a preference for sons has led to a serious imbalance of the sexes. In 2010 half of all middle-aged men in South Korea were single, a fivefold increase since 1995. The birth rate has fallen to 1.3 children per woman of childbearing age, down from six in 1960. It is one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. Without immigration, the country’s labour force will shrink drastically.

The government is the biggest enthusiast for a multi-ethnic country. Its budget for multicultural families has shot up 24-fold since 2007, to 107 billion won ($105m). Some 200 support centres offer interpreting services, language classes, child care and counselling. School textbooks now include a section on mixed-race families. And in 2012 mixed-race Koreans could join the army for the first time. When four Mongolians working illegally in South Korea pulled a dozen Korean colleagues from a fire in 2007, locals urged the government to grant them residency (it did).

Still, assimilation remains elusive. Four in ten mixed-race marriages break down in the first five years, according to a survey by the Korean Women’s Development Institute, a think-tank. In 2009 almost a fifth of children from mixed-race households who should have been in school were not. Many mothers have limited Korean. And discrimination lurks.

The government is now tightening up the marriage rules. Last month two new requirements came into force: a foreign bride must speak Korean, and a Korean groom must support her financially. Koreans are now limited to a single marriage-visa request every five years.

Critics say making marriage more difficult will only serve to speed up the greying of the workforce. The pool of eligible women will shrink, says Lee In-su, a marriage broker in Daegu in the south-east. Most foreign brides come from rural areas lacking language schools. Meanwhile, competition for brides from China, where men also outnumber women, is fierce.

In fact, the number of Korean men taking foreign brides is dropping, from 31,000 a year in 2005 to 18,000 last year. And nine-tenths of matches are now urban, says Mr Lee. Vietnamese girls no longer want to languish in the Korean countryside, says Kim Young-shin of the Korea-Vietnam Cultural Centre in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital. They like watching Korean dramas and listening to K-pop—urban pursuits.

As for Korean clients, says Lee Chang-min, a broker in Seoul, they are increasingly better educated and better-off; some are among the country’s top earners. Many are simply on lower rungs of the eligibility ladder in a culture captivated by credentials, whether in looks, age or family connections.

Others, Mr Lee says, are wary of the stereotype of the doenjangnyeo (a disparaging term for a class of Korean women seen as latte-loving gold-diggers). They prefer a wife who can assume a more traditional role than one many Korean women are nowadays willing to play. These men, the brokers lament, are now more likely to be introduced to their foreign wives through friends than through brokers. Perhaps a modest win for melting-pot Korea after all.